Intro to Forecasting

Imagine trying to model monthly ice cream sales. How would we go about this? A good first thing to consider is the number of cones we’d expect to sell in a “typical” month. Moreover, if ice cream becomes more popular or the store introduces some great flavors, we might expect the monthly sales to grow month over month! Finally, we might consider when people tend to buy ice cream — sales likely tend to be highest around mid-summer when temperatures are hottest in most areas, and lowest around mid-winter when temperatures are coolest (unless you’re a winter-only ice cream eater like me).

There are obviously (sidenote: Random noise, for instance.) at play here, but “number”, “growth”, and “timing” are the “big three” and have their own names, respectively: a level $l$, (sidenote: The canonical variable for trend seems a little strange at first, but since "t" is reserved for time, this label comes from the slope component of a linear polynomial "a + bt".) $b$, and seasonality $s$.

We can represent a time series $y$ as the sum of these “big three”. As such, if we were to subtract the seasonality component from a time series, we’d be left with just a linear polynomial. There are also multiplicative forms of forecast models, though they are out of scope for this article.

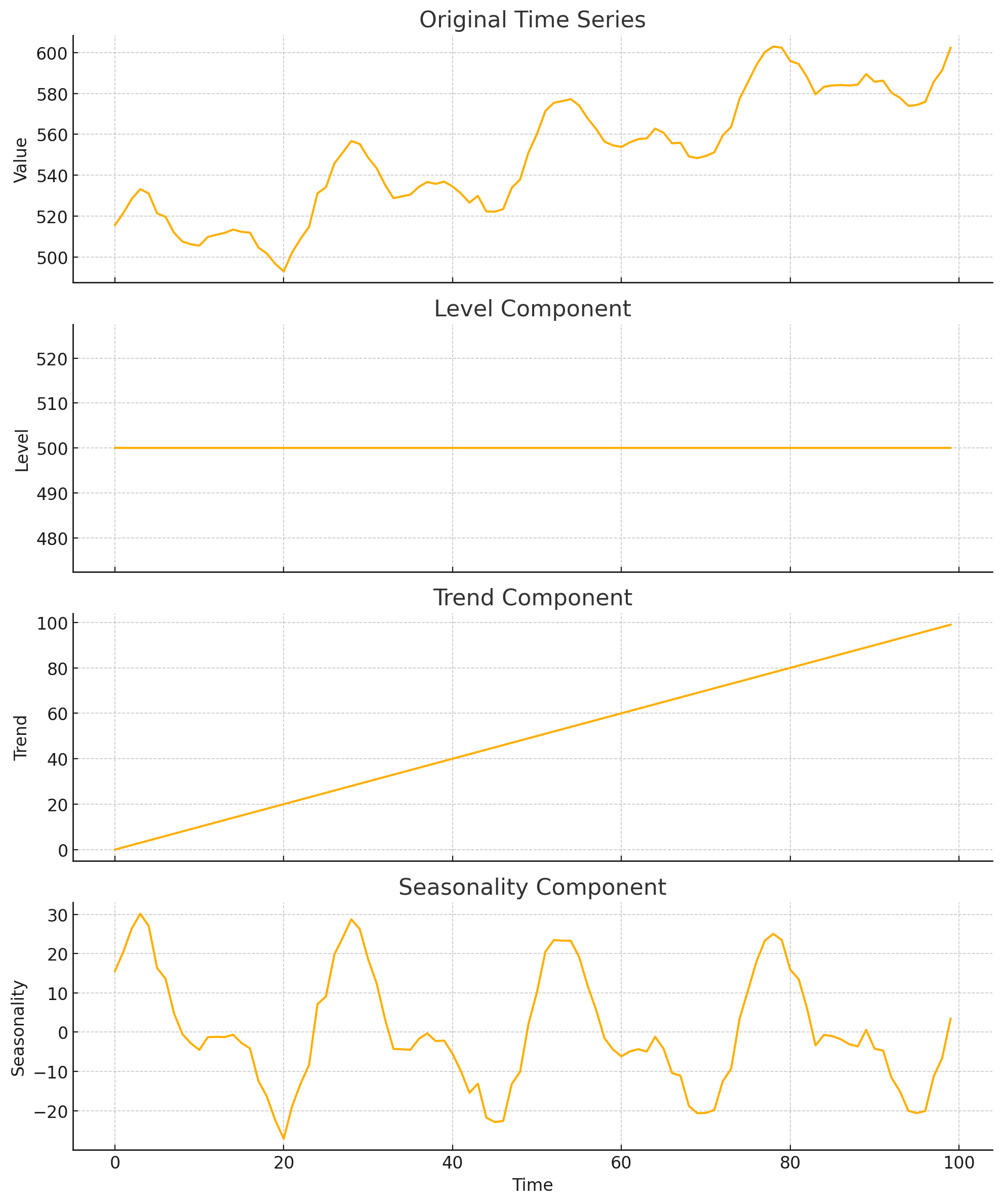

Consider a very idealized example of this decomposition:

Holt-Winters

Logically, we probably trust recent data more than past data! In the simplest intuitive case, this means we need some value $x_t$ to depend on both our current observation $o_{x_t}$, scaled by how much we trust it, and some previous relevant value $z_{t-1}$, scaled by how much we don’t trust it. Let’s let our (sidenote: These are canonically called "smoothing parameters.") be values between $0$ and $1$, inclusive, and be denoted by a Greek letter. Then, the above “trust” idea can be written for any general variables $x, z$ and trust value $\tau$ as follows:

$$ x_t = \tau o_{x_t} + (1-\tau)z_{t-1} $$As expected, $\alpha=1$ means we perfectly trust our current observation, and we don’t consider our previous related values at all; and $\alpha = 0$ means we don’t trust our current observation at all, instead relying entirely on our previous relevant values. I’ll refer to this relationship as a (sidenote: This is term was coined for brevity and intuition's sake.) of $x$ and $z$.

The idea of a trust-based blend makes modelling our “big three” components really simple! All we have to do is identify the correct in-context representations of $o_t$ and $z_{t-1}$ for each, then create a trust-based blend of them! For simplicity, let’s start with trend.

Since the trend is the slope component of our model, and since the time delta between observations is $1$ unit, our current observation of trend is $o_{b_t} = \frac{l_t - l_{t-1}}{1}$. Then, since we also want to consider yesterday’s slope in our prediction, we can create the simplest trust-based blend of $o_{b_t}$ and $b_{t-1}$:

$$ b_t = \beta^*(l_t - l_{t-1}) + (1-\beta^*)b_{t-1} $$It’s as easy as that! Let’s move on to seasonality.

Leaning on the additive nature of the time series, as discussed earlier, subtracting the linear polynomial component yields just the seasonality component. Thus, our seasonality observation is $o_{s_t} = y_t - l_{t-1} - b_{t-1}$. By the definition of periodicity, we should be able to predict the current value by referring to the corresponding past value exactly one season ago! Let’s call the number of observations per season $m$. Then, the corresponding seasonal component, one season ago, is simply $s_{t-m}$. Then, we can calculate $s_t$ via trust-based blending:

$$ s_t = \gamma(y_t - l_{t-1} - b_{t-1}) + (1-\gamma)s_{t-m} $$Finally, we can tackle level. Again, subtracting the seasonality component yields the linear polynomial component. Thus, our level observation is $o_{l_t}=y_t-s_{t-m}$. Since $b$ is the slope of the linear model with which we we predict levels, we’d like to create a trust-based blend of our actual level observation and our previous forecast of the level. Since the time delta between observations is $1$ unit, our forecast of the previous level is $l_{t-1} + b_{t-1} \cdot 1$:

$$ l_t=\alpha(y_t-s_{t-m})+(1-\alpha)(l_{t-1} + b_{t-1}) $$These three recursive relations make up the core of the Holt-Winters forecast method! To forecast future values $\hat{y}$ $f$ steps ahead, we simply add up each of our “big three” components:

$$ \hat{y}_f = l_t + fb_t + s_{t+f-m} $$where $t$ in this instance represents the last observed point. Again, our seasonal value is taken from the equivalent value from last season.

Closing

Just like that, we’ve derived a lightweight, transparent model that respects both steady growth and familiar seasonal swings – no black-box complexity required! For these exact reasons, Holt-Winters is used extensively in use cases like demand forecasting (e.g. retail sales, inventory planning), energy load prediction, web-traffic smoothing, budget planning, and even anomaly detection in server metrics!

To test your understanding, see if you can answer these conceptual questions!

- Why is Holt-Winters sometimes referred to as “triple exponential smoothing”? Hint: consider the mathematical implications of the recursive nature of these relations.

- What post-fit patterns in the residuals of an optimized Holt-Winters model would indicate that the method is a poor choice? Hint: what post-fit residual patterns would indicate that it’s a good choice?

- How might you transform your time series to convert this additive version of Holt-Winters into a “multiplicative” one without changing the recurrence relations?

If you’re curious to learn more, feel free to research the topics below:

- Initialization strategies. We established recurrence relations, but we didn’t discuss initial values!

- Smoothing parameter selection methods. How, algorithmically, should we select our trust values?

- Multiplicative vs. additive recurrence relations. Why would you use one or the other?

- Model validation.

Code

python code snippet start

import numpy as np

class AdditiveHoltWinters:

def __init__(self, alpha: float, beta: float, gamma: float, obs_per_season: int):

"""

alpha, beta, gamma: Smoothing parameters for Holt-Winters.

obs_per_season: The number of observations that make up a season.

e.g. monthly data with yearly seasonality --> obs_per_season = 12

e.g. daily data with weekly seasonality --> obs_per_season = 7

"""

self.alpha = alpha

self.beta = beta

self.gamma = gamma

self.m = obs_per_season

self._is_fit = False

def fit(self, series: list):

"""

Fits the additive Holt-Winters model using the smoothing parameters it was initialized with.

"""

if self._is_fit:

raise Exception("This model has already been fit!")

y = np.array(series)

N = len(y)

m = self.m

# Convenience

alpha = self.alpha

beta = self.beta

gamma = self.gamma

# Level, trend, season

l = np.zeros(N)

b = np.zeros(N)

s = np.zeros(N)

# Initialize the level, trend, and season by regression fit of a first-order

# Fourier series, as suggested by Hyndman in the article below. The intution for

# this lies in the fact that periodicity should nudge you towards sinusoids. We

# simplify by only considering the first harmonic

# https://robjhyndman.com/hyndsight/hw-initialization/

# l_0 + b_0*t + A*cos(2pi*t/m) + B*sin(2pi*t/m)

X = np.column_stack(

[

np.ones(N),

t := np.arange(N),

np.cos(2 * np.pi * t / m),

np.sin(2 * np.pi * t / m),

]

)

l[0], b[0], A, B = np.linalg.lstsq(X, y)[0]

for i in range(m):

s[i] = A * np.cos(2 * np.pi * i / m) + B * np.sin(2 * np.pi * i / m)

# Ensure that the seasonal factors have no net change on the average level

s[:m] -= s[:m].mean()

for t in range(1, N):

if t < m:

l[t] = y[t]

# Initialize by carrying forward the trend

b[t] = b[t - 1]

# Optionally, clobber the computed seasonal values. You may want to do this

# if your initial seasonal estimates are unstable or the Fourier fit is poor

# s[t] = s[t-1] # To do so, uncomment this line

continue

# https://otexts.com/fpp2/holt-winters.html

l[t] = alpha * (y[t] - s[t - m]) + (1 - alpha) * (l[t - 1] + b[t - 1])

b[t] = beta * (l[t] - l[t - 2]) + (1 - beta) * b[t - 1]

s[t] = gamma * (y[t] - l[t - 1] - b[t - 1]) + (1 - gamma) * s[t - m]

self.N = N

self.l = l

self.b = b

self.s = s

self._is_fit = True

def forecast(self, f: int):

"""

Forecasts f steps into the future.

"""

if not self._is_fit:

raise Exception("This model must be fit before it can forecast!")

f = np.zeros(f)

for h in range(1, f + 1):

# In essence, reference the equivalent value from last season

i = self.N - self.m + h

f[h - 1] = self.l[-1] + h * self.b[-1] + self.s[i]

return f

# For testing purposes, consider the following initialization for quarterly data:

# test = AdditiveHoltWinters(alpha=0.3, beta=0.1, gamma=0.1, obs_per_season=4)python code snippet end