Cracking Dynammic Programming

So what is Dynamic Programming Anyways?

Amateur programmers (like myself), recall dynamic programming as the technique where smaller sub problems are discovered, solved, and memorized to assemble the solution to a larger, complex problem. While the formal definition provides a great overview of why dynammic programming works, it does not explore deeply how dynamic programming simplifies problem complexity and why the technique is so efficient. Before we understand those concepts, we must formalize a tool that we use to visualize DP problems. Enter: the Directed Acyclic Graph

An Introduction to Directed Acyclic Graphs (DAGs)

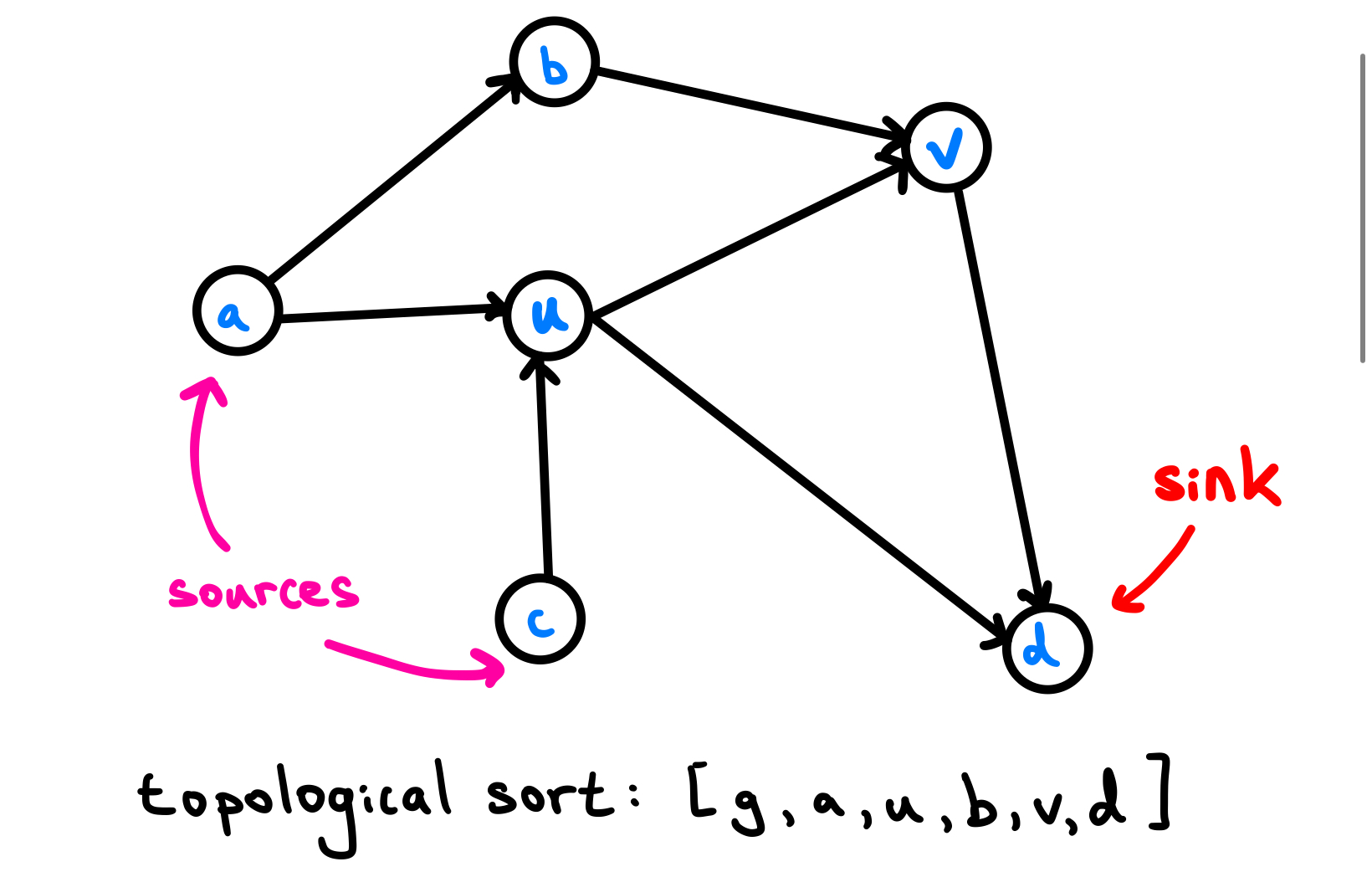

Solving problems is all about identifying connections between bits of information. What better structure can we use to portray connections within a set of objects than a graph? More specifically, a Directed Acyclic Graph is a directed graph with no (sidenote: A graph cycle with all edges pointing in the same direction) . In this article, we call $u$ a pre-requisite of $v$ if there exists an edge going out from $u$ to $v$. Likewise, $v$ is a dependency of $u$.

It should be intuitive why a DAG is often referred to as a dependency graph by programmers. It provides a structure that encapsulates information about all the dependencies that is required by a certain service, process, and in our case, problem. A topological sort of a DAG is an ordering of the vertices $V$, such that all the dependencies of $u$ appears before $u$ itself. Such a sort allows us to traverse the graph from pre-requisite to dependency. A toplogical sort exists for all DAGs, but not all directed graphs. Do you see why?

The Topological Sort Algorithm $O(V + E)$

- Perform a DFS traversal from every vertex in the graph while maintaining marked vertices across traversals.

- Record the DFS Post-Order of each traversal.

- Concatenate the Post-Order traversals and reverse the order.

This algorithm works as DFS only ever reaches a vertex when all of it’s pre-requisites have already been visited. Thus, the reverse of the Post-Order gives us an ordering where all pre-requisites come before a dependency. Hence, a topological sort.

Tying it All Back to Dynamic Programming

Recall that in a DP problem, we have sub-problems that we’d like to solve to construct a solution to a larger problem. What makes DP so challenging, is identifying the sub-problems, and solving them in the correct order.

- Identifying Sub-Problems: Perhaps the main challenge of DP, it helps to note down all elements of problem space itself. This could be all the elements present within a vector, or all numbers in a particular range. Think about if there is a “atomic element” that has a trivial solution, that would serve as a base-case. Now for each problem, consider what defines another problem as a dependency, or as a pre-requisite. This clearly defines the “sources” of your DP problem, and establishes a means of drawing the connections between sub-problems.

- Find a topological sort: Discover the order in which you must solve the sub-problems in. This would be a topological sort of the DAG you have visualized. In some problems, the input may already be topologically sorted. In other problems, the coder must topologically sort first.

- Apply what you know: Using the logic that solves the base case, solve the sub-problems according to the topological order. This would ensure that you can solve all sub-problems for a test case, while avoiding redundant calculations. You are done!

Why do this?

Visualizing dynamic programming questions through the DAG lens allows us to capture the underlying structure of the problem. Such problems are typically recursive in nature, and capturing dependency relationships allow us to create a logically sound order of how to solve a problem. This applies not just to coding questions, but in real life as well. You wouldn’t put the dishes away and then wash them. You’d wash them first, scrub them off, organize them, and then put them away (unless you are me).

Examples

Longest Increasing Subsequence

Problem: Given an array $A$ of values, find the longest increasing subsequence, that is, a consecutively increasing subsequence $(a_n)$, where for $i\in {1,...,n-1}$, $a_i>a_{i-1}$. Remember:

- Find subproblems

- Topologically Sort

- Apply your logic

Solution: In this problem, for elements $a_i,a_j\in A$, $a_i$ is a pre-requisite of $a_j$ if $x$ satisfies the two conditions:

- $j > i$

- $a_j > a_i$

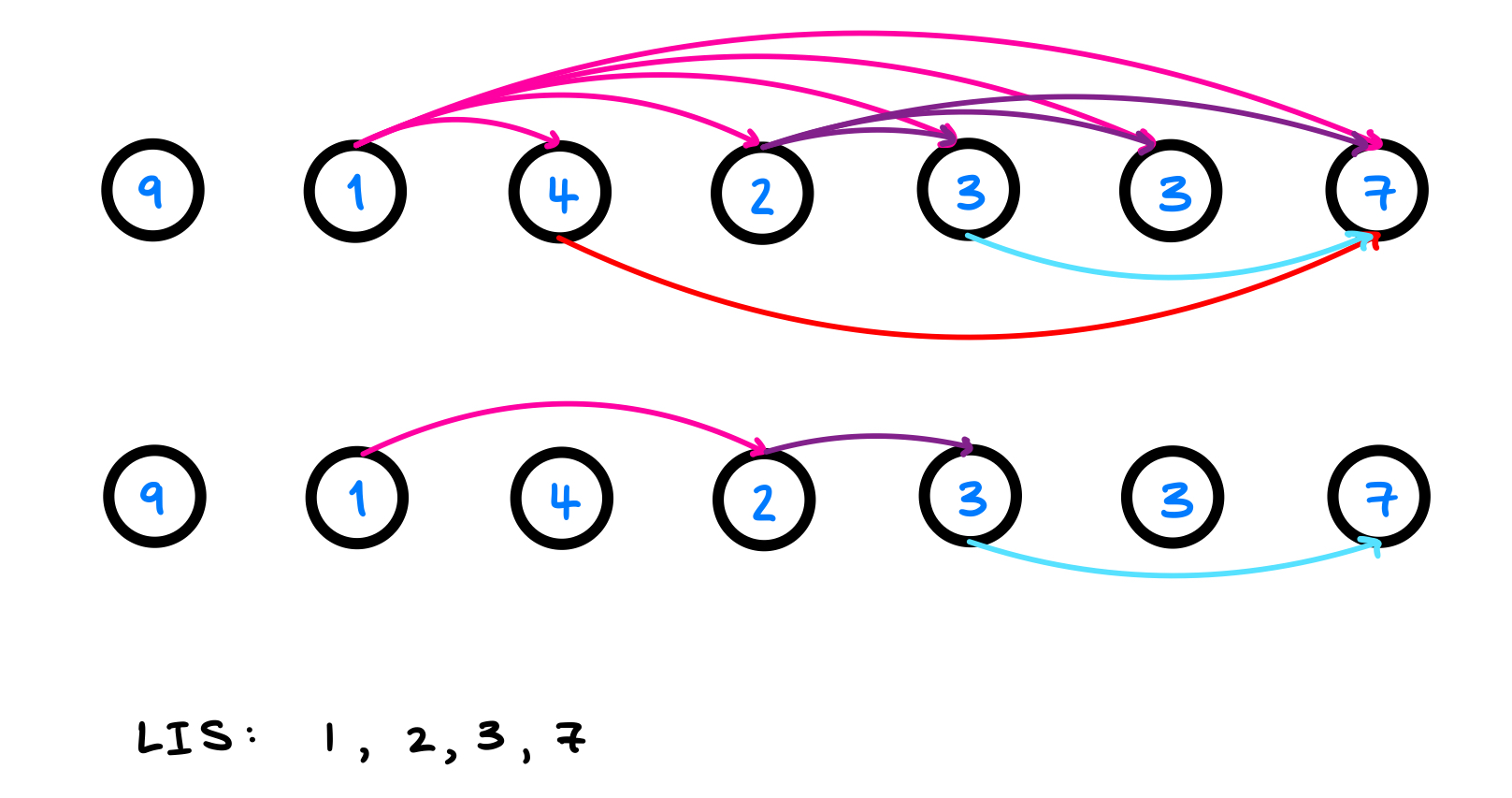

It may not be obvious, but the input data is already topologically sorted for us. The input array has increasing element indices, so condition 1 is satisfied. We do not even need to sort condition two, as we may just manually filter out larger preceding elements. Here is a linearization of the topological sort of the DAG for test case $[9,1,4,2,3,3,7]$.

As we can see, the longest increasing subsequence has a length of 4, more importantly, this is the same as the length of the longest path in our DAG! Hence, we have applied a very important concept in computing theory– We used (sidenote: Transforming an often challenging problem into an existing problem whose solution is known) to transform the Longest Increasing Subsequences problem to the DAG longest path problem!

To do this, on each index $i$, we tabulate the Longest Increasing Sequence that ends at and includes the element at $i$. To calculate this length, we iterate again over all preceding indices. We find the longest increasing subsequence in that subarray, and we just add one to that value to find the Longest Increasing Sequence at index $i$.

cpp code snippet start

int lengthOfLIS(vector<int>& A) {

vector<int> dp(A.size(), 1);

for (int i = 1; i < A.size(); i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) {

if (A[j] < A[i]) {

dp[i] = max(dp[i], 1 + dp[j]);

}

}

}

sort(dp.begin(), dp.end());

return dp[nums.size() - 1]

}cpp code snippet end

$\boxed{ }$

Maximum Height by Stacking Cuboids

Problem: Given $n$ cuboids where the dimensions of the $ith$ cuboid is $A[i] = [width_i, length_i, height_i]$ (0-indexed). Choose a subset of cuboids and place them on each other.

You can place cuboid $i$ on cuboid $j$ if $width_i <= widthj$ and $length_i <= length_j$ and $height_i <= height_j$. You can rearrange any cuboid’s dimensions by rotating it to put it on another cuboid.

Return the maximum height of the stacked cuboids.

Solution: Once again, we note down what we know about this problem, and any intuition we have. We are given the freedom to freely rotate cuboids, moreover, cuboids may only be stacked on one another if all three dimensions of a cuboid are smaller or equal to the cuboid it is being stacked on. This points at a greedy/DP solution.

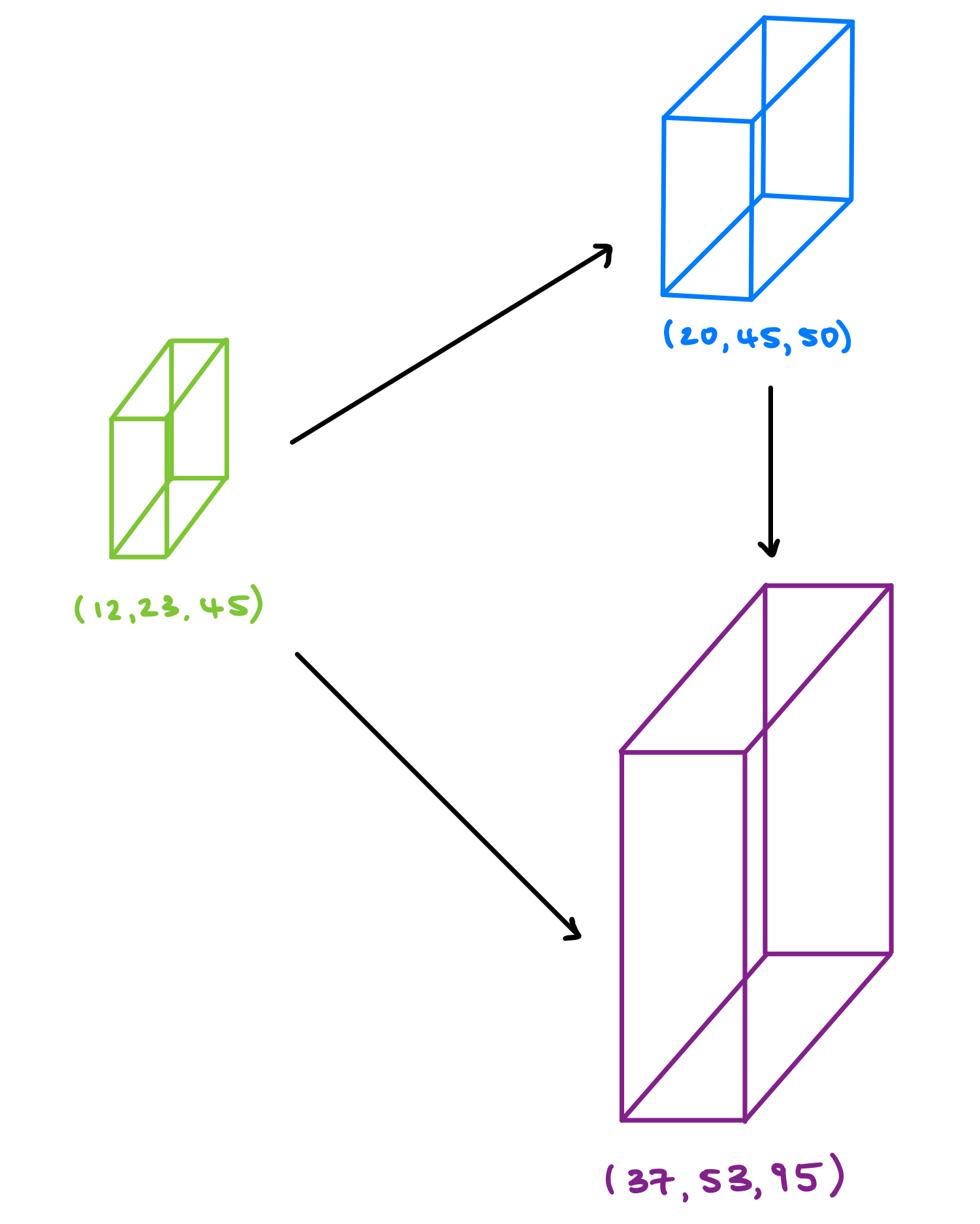

To maximize the height of what we can achieve, we first sort all triplets such that the last index indicates height. This automatically ensures all cuboids have been rotated such that they are standing at their tallest. From here, we apply what we know about DAGs and DP. We try to visualize the test case $[[50,45,20],[95,37,53],[45,23,12]]$, which after sorting the individual elements, becomes $[[20,45,50],[37,53,95],[12,23,45]]$. Now for each pair of elements $x,y$ in our problem space, $x$ is a pre-requisite for solving $y$ iff all dimensions of $x$ are bigger than $y$. Our DP-DAG would look like this:

We note that the solution $190$ is simply the three cuboids rotated, and stacked on top of each other. This also happens to be the path in our DAG that maximizes height.

It would be complicated to write a topological sort for the graph, but we can simplify this. Instead of running DFS post order, we can look at our sorted cuboids and declare that they have format $[length, width, height]$ . Now, we can just sort the array based on the array array values, such that cuboids with smaller length/width/height comes before cuboids with larger dimension.

We now iterate through this sorted list, and calculate the maximum height of a stack with the cuboid at index $i$ on top. We also only update the maximum height, after we verify that all 3 dimensions are larger on the previous top cuboid that we are stacking on. This enforces that we only consider relations outlined by the edges in the DAG, while never having to implement the topological sort ourselves.

cpp code snippet start

int maxHeight(vector<vector<int>>& A) {

for (auto& cube : A) {

sort(cube.begin(), cube.end());

}

A.push_back({0, 0, 0});

sort(A.begin(), A.end());

vector<int> dp(A.size(), 0);

int res = 0;

for (int i = 0; i < A.size(); i++) {

for (int j = 0; j < i; j++) {

if (A[j][0] <= A[i][0] && A[j][1] <= A[i][1] && A[j][2] <= A[i][2]) {

dp[i] = max(dp[i], dp[j] + A[i][2]);

res = max(res, dp[i]);

}

}

}

return res;

}cpp code snippet end

$\boxed{ }$